On March 31st I joined Huib Schoots and Pascal Dufour in picking up James Bach from Schiphol Airport and driving him to his hotel in Dordrecht. Having met Cem Kaner (briefly) and Michael Bolton (several times) I was looking forward to meeting James in person and I was not disappointed. Conversation en route was vivid and fruitfull and continued during dinner at Villa Augustus and later on April 3rd after an Agile Meetup with presentation by James at Codecentric. During dinner James had offered Pascal a challenge and later that evening he offered me the following challenge on twitter:

after an Agile Meetup with presentation by James at Codecentric. During dinner James had offered Pascal a challenge and later that evening he offered me the following challenge on twitter:

Explain dendogram-based testing

My first thought was “What’s a dendogram?” So I googled it and saw something I had long forgotten from when I studied Social Sciences and certainly had never used in testing.

So for those of you who requested me to blog on testing and the social sciences this is my first post on the subject.

For all the others with this post I want to share my answer to the challenge with you and some of the reactions I got from James on it.

What is dendogram-based testing?

To answer this question I will start with a short description of what I understand a dendogram is. Followed with a description of how I think this could be used in testing.

Dendogram

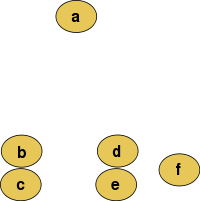

A dendogram is a visual representation of data that shows hierarchical clusters of, potentially before unknown, groups of data in a cluster tree diagram. A picture of such a diagram is shown below.

Cluster analysis, for a dendogram, starts with a data matrix, where objects are rows and observations are columns. From this beginning, a table is constructed where objects are both rows and columns and the numbers in the table are measures of similarity or differences between the two observations.

From measurements to relative observation results

You can then place the results in a cloud of n points or in a matrix and put each point in a class of its own (having n classes, each containing a single point). Then, look for the closest two classes (for a given distance, for instance the relative distance between measurement of a feature– but other distances will give other results, perhaps more appropriate for some data sets) and join them into a new class. You now have n-1 classes, all but one containing a single element. Then iterate this activity until you reach a single set containing al the classes. The result is presented as a dendogram: the leaves are the initial 1-element classes and the various “levels”) of the dendogram are various clustering’s of the data, into a decreasing number of classes.

It is also possible to calculate the distances and their relationships with the use of Euclidian algebra. This uses a number of formulas to calculate hierarchical distance between the data (clusters). But besides the relative complexity of the calculation I prefer to use the more visual and intuitive approach.

Dendogram-Based Testing

The concept of clustering data in a hierarchical form and thus grouping it based on some measured characteristic opens a number of possibilities for testing. All of these possibilities have in common that both the activity of clustering of data and the end result, be it in numbers or a visual representation, form an additional source of information about the subject under test. The kind of information will largely differ based on the chosen measurement. With regard to testing I see the following, extendable list of areas for observation and measurement:

- The relationship between functionality and code

Where code is differentiated into several elements such as (that are more or less commonly used):

- Type of input

- Used variables

- Classes

- Functions

- Methods

- Etc.

- The relationship between test cases and code

- The relationship between functionality and GUI elements

- The relationship between defects and code

- The relationship between defects and their cause of failure

The clusters of information that you get out of it provide the following information and activities for testing:

- The different clusters of information can suggest different testing techniques

- The different clusters of information can suggest different testing missions

- The different clusters of information can suggest different elements of reporting

In essence the information derived from a dendogram is dependent from the kind of observation and measurement you choose, the skill you have in identifying the clusters and patterns and the skill to adapt your testing activities. In any case it forms a new oracle to be used in software testing.

The above description was made before I read the following document, that I had avoided on purpose: http://melindaminch.com/docs/thesis.pdf

In my, opinion the thesis is a nice academic exercise that adds insight to testing, but lacks sufficient practicality for use in every day testing. But I will study it more carefully at sometime in the future and I will see if there is an opportunity to use HCE 3.0 that I have downloaded.

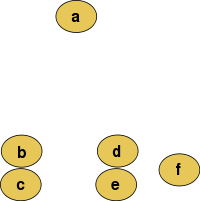

For now I prefer the more general intuitive approach as described above and instead of the more elaborate HCE program I would use a reverse mind map.

Giving me the below, originally not in my answer included, graphical steps:

Which translates into

Which translates into  the following Dendogram

the following Dendogram

James response to my answer

Below I have pasted the, unedited, response James gave my to my answer.

Jean-Paul, I am impressed. This is an excellent answer. I concur with your reasoning. I’d like to try using dendograms in testing, when the opportunity arises.

The reason I gave you this challenge is that we who aspire to excellence must be comfortable describing test techniques that don’t yet exist– in other words, we must be confident in our ability to invent test techniques as needed. This is a challenge that cannot be solved well using Google, since almost nobody has applied dendograms to testing, and the one reference you cite does a poor job of it.

By researching this and replying as you did, you have marked yourself as a leader in the Context-Driven community. Thank you.

— James

Needless to say that I am proud to receive such a response. And I feel strengthened in my drive to grow and learn as tester and as a member of the context-driven community.