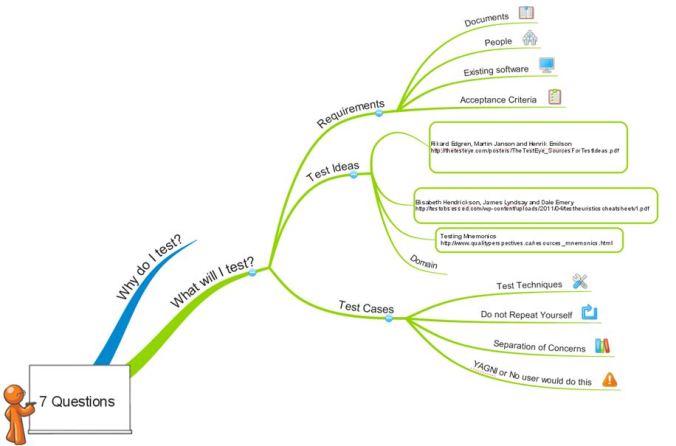

In the previous post I addressed why you test. In this post I will address what you are going to test. In the sections below I will hand you a number of ideas. Some of them are well-known in main stream testing and other may be a bit more out of the box to some of you.

Requirements

I think I am not exaggerating if for most testers and stakeholders covering the written requirements with test cases still is what you as a tester should do. This line of thought is more generally known under the title of Requirements Based Testing. As a definition this could be described as:

Requirements-based testing (RBT) process addresses two major issues: first,

validating that the requirements are correct, complete, unambiguous, and logically

consistent; and second, designing a necessary and sufficient (from a black box

perspective) set of test cases from those requirements to make sure that the design and code fully meet those requirements

Followers of this approach do admit that requirements, or rather documents, are hardly ever complete and that testers almost never have the possibility to design and execute all possible tests. This last insight is the foundation of an approach called Risked Based Testing (or sometimes called risk and requirements based testing). You can find more information on it here, here, and slightly more hidden in here. But personally I like this interpretation of risk based testing, by J. Bach, best.

A major advantage of risk based testing, and in my opinion essential in finding out what to test, is that it is based not only on documents as a source, but that it is based on people as a source of information. People are a major source of requirements and especially of requirements that matter to them. Documents can tell you a lot, but people can tell you what’s missing in them, how to give meaning to them and therefore paint you a more complete picture.

A good source of information, besides risks, that people can also give is how they current software or the manual operation that they use to solve the problem now. Often this will be the basis for the acceptance criteria that they formulated, or that you will formulate together with them for the new software. Acceptance criteria are useful to give direction and focus to your testing and are mandatory elements in the structure of your testing report.

You the tester

Finding out what to test is not only about bringing the subject under test and its information to you the tester. It is also about what you bring to the subject. What knowledge of the domain do you already have? What test ideas or mnemonics do you know that are useful in the context of your subject?

Sources for Test Ideas and mnemonics

The list below has some online sources you can use and fit into your situation. Use them, adjust them and come up with your own ideas.

- Test Heuristics Cheat Sheet – Elisabeth Hendrickson

- Heuristic test strategy model – James M. Bach

- ET dynamics – James M.Bach, Jonathan Bach, Michael Bolton,

- The Little Black Book on Test Design – Rikard Edgren

- You Are Not Done Yet (checklist) – Michael Hunter

- 37 Sources for Test Ideas – Rikard Edgren, Martin Jansson, Henrik Emilson

- Software Quality Characteristics – Rikard Edgren, Martin Jansson, Henrik Emilson

- Testing Mnemonics Listing – Lynn McKee

- Several Checklists – Software QA and Testing Resource Center

- Touring Heuristic – Michael D. Kelly

- 8-layer testing model – Steve Green (video)

Test Cases

There are many definitions for a test case. My personal one is: “A test case is the execution-able version of a test idea. A test case aims at gathering information about the test ideas relation to the subject under test and the value of that information to the stakeholders.” If and how much of a test case is (pre-)scripted is based upon personal preferences, the test idea itself and the context in which it is executed. Attention should in any case not go towards the quality of scripting of a test case, but towards the relevance and value of the information that is delivered by the test case.

Designing test cases, scripted or otherwise, takes skill and experience. I therefore believe that as a start a good tester should have a base of test design skills and a testing mindset. As a start I would like to recommend the following literature:

- TMap Next (Chapter 14) – Tim Koomen, Leo van der Aalst, Bart Broekman, Michiel Vroon

- Lessons Learned in Software Testing – Cem Kaner, James Bach, Bret Pettichord

- Essential Software Test Design – Torbjörn Ryber

- What is good test case? – Cem Kaner

When working on test cases there are a few principles that I like to keep in mind. The DRY principle. DRY stands for “Do not Repeat Yourself”. If test cases draw their value based on the information they offer it is not useful to use variations of tests that do not deliver new information. This principle does have a catch as you do not always know in advance if a variation does or does not deliver new information or not.

Separation of concerns is another principle that lets you focus your attention upon some (single) aspect. This does not mean that the other aspects are ignored. It means that you address the subject under test with a singular point of view, deeming the other’s irrelevant at that point in time while not forgetting that relationships might exist.

Finally I am always interested in mentions like “You Ain’t Going to Need It” (YAGNI) or “No user would do that” popping up in any design discussion between other team members. The areas discussed are an interesting area to start investigating.

This concludes this third post of the Seven Questions series.