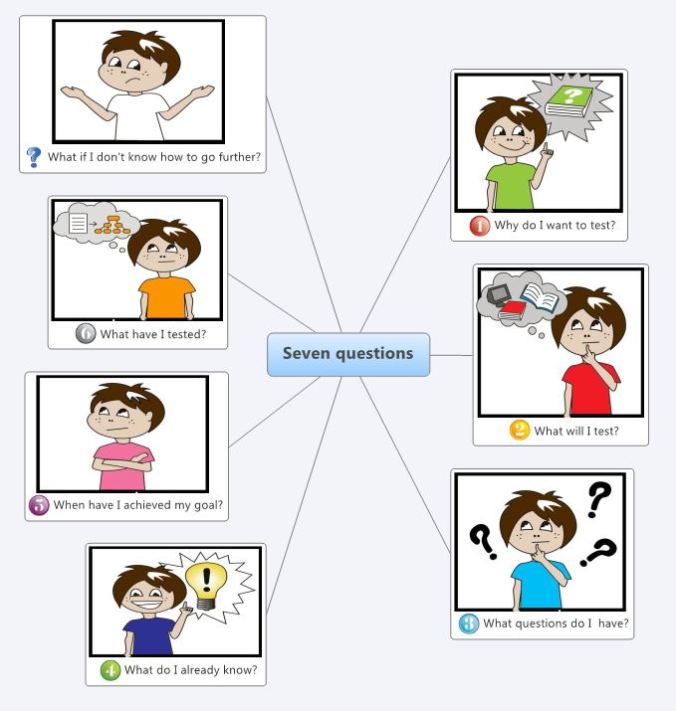

Reasons for testing

The question why something is tested has kind of a schizophrenic nature to it. Its answer is either so obvious that the question itself is ignored or it is so cumbersome that testers rather avoid to answer it. The latter is mostly the case if testers have to defend why testing is done in the first place. I cannot provide you with ready made answers for this, because the answer depends too much on the circumstances and context of your situation. What I can tell you is that it is worth while for you to figure out why your specific subject under test needs testing. If you can answer this for your specific situation, then the contextually acceptable general answer should be able to be derived from it.

What to take into consideration?

One of the more common ideas on why software testing is conducted is that it’s done to find bugs. The idea is that the fact that you do or do not find more then a certain amount of bugs in time is a measurement for release readiness. Obviously such a amount of bugs doesn’t say anything about how serious the remaining bugs are nor does it say anything about the bugs you did not find. Already more than 40 years ago Edsger W. Dijkstra (1969 p.16 and 1970) discovered that software testing can show the presence of bugs, but never their absence .

Another reason to do software testing is that there is some internal or external reason to do it. A standard, law or regulation exists that either states that you have to test or whose interpretation makes management believe that you should do tests, often in a certain predefined way, to meet the rules. This is not a bad thing as an external reason for testing.

A better, more internal, reason for testing is that the software is tested to provide information. Better still Information that is meaningful with regard to the product itself, its intended use, its real use, its potential (miss)use and related to the value this has to which stakeholders.

Your Challenge

It is your challenge as a tester to find out what the information is that the stakeholders value. Then extend this with the information they should value, even if for reasons thus far unknown to them. And finally to find a way how to provide that information so that its relevance and value is delivered to them in a meaningful way.

With some well-directed extra effort the value of testing can grow. Both to the tester and to the stakeholders.

Finding the right reason

Way back in 1998, with the introduction of the Euro to the financial markets I came in contact with software testing for the first time. As a business acceptance tester I was responsible of judging whether the new programs actually had the desired functionality and if we could work with them. Especially that latter part had the focus of my attention. Being one of the users myself and being involved in the requirements design of the product I found it easy to understand why this had to be tested and what value to look for.

More often than not software testers are not so familiar with the everyday practical needs and demands of the product they are working on. In this case I have two approaches that I prefer to use and that have served me well in the past. The first is to approach testing heuristically, with for instance the Heuristic Test Strategy Model, and explore the product with helpful mnemonics like FEW HICCUPPS . The second approach is to converse and to keep on conversing with the stakeholders and ask them all they need to know.

Who else would know better what matters to them than the people who matter (to the product and/or the project) themselves.

started with gathering in the grand cafe, dinner and a lightning talk by myself in the conference room. I had planned and prepared the lightning talk to be about the summarized content of my EuroSTAR conference talk

started with gathering in the grand cafe, dinner and a lightning talk by myself in the conference room. I had planned and prepared the lightning talk to be about the summarized content of my EuroSTAR conference talk